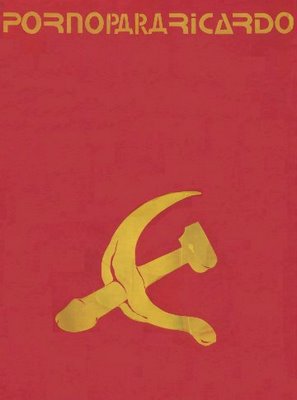

The following is an interview with the punk Cuban band Porno Para Ricardo, and more specifically its firebrand leader Gorki Águila Carrasco. It was published [in Spanish] for the internet magazine Cuba Encuentro. It is interesting that bands such as Audioslave [will not provide link] have been allowed to play in Cuba, while members of home grown bands like Porno face actual jail time for playing their brand of music and without mincing words. Regardless, Gorki continues to be defiant, calling things by what they are, and there are no regrets. Cuba needs more Gorkis, just look at the band's logo, does it offend?

The following is an interview with the punk Cuban band Porno Para Ricardo, and more specifically its firebrand leader Gorki Águila Carrasco. It was published [in Spanish] for the internet magazine Cuba Encuentro. It is interesting that bands such as Audioslave [will not provide link] have been allowed to play in Cuba, while members of home grown bands like Porno face actual jail time for playing their brand of music and without mincing words. Regardless, Gorki continues to be defiant, calling things by what they are, and there are no regrets. Cuba needs more Gorkis, just look at the band's logo, does it offend?H/T: Alberto – EC reader and commentator.

Here is a translation of the article, the Spanish version appears after this.

Gorki Águila, leader of the band Porno Para Ricardo, affirms that he does not have to resort to any poetic means to point out who is responsible for the “hell that Cuba is in.”

After paying the taxi fare, we entered the crumbling and in need of repair Soviet Union era concrete skyscraper. The rockers were waiting inside. They have been discussing how to continue with their music. Yesterday, the police issued them a citation that foretells nothing good about their objective of openly continuing to produce their music.

The document with the official seal, lies on top of the table, it has the appearance of being nothing more than a friendly invitation.

What is it about, exactly? We asked Gorki Águila Carrasco, singer of the group Porno Para Ricardo, in an interview for “Encuentro en la Red.”

It is a citation from the police with the seal of the Cuban Republic, from the Ministry of the Interior, of the National Revolutionary Police. A certain Lieutenant Torres signs it. I have been ordered to appear there tomorrow at 11:00 hours.

What exactly do they want from you? Do they want to force you not to ever play again?

Gorki: All this started when we were accused of disturbing the peace and tranquility –the police told us that the neighbors were complaining about the noise during the night. Now they want to tell us something about the words in our songs that attack Fidel Castro. At one time, the police very cynically told us: “Whatever your feelings about the Cuban revolution, you are forbidden from saying it in public.”

Then, the words that you write speak directly about Fidel Castro?

G: Yes. We have a song dedicated to our commander in chief, that mentions his complete name and it is states very clearly that he is a son of a whore. All the art that is created in this country, in some way, it is hidden in double entendre, and I have grown tired of those poetic words filled with indirect insinuations. The time has come to call it by what it is. What I am interested in saying the most with the words in our songs is that the hell that we live in has a first name and last names: Fidel Castro Rúz. I do not have to resort to any poetic means to say it.

May I quote you directly in the article?

G: Of course, yes, that is what I am saying.

Have you played the Castro song in public?

G: No, because it would be virtual suicide. Nonetheless, if we record it in the end I will end up in the hands of some official. That is why that we have received the citation from the police. Their strategy is to intimidate us, to blocks us with all the resources at their disposal. We are already prohibited from playing in concerts and now they do not even want us to rehearse.

Is this the first time that you have been interrogated by the police?

G: This is officially the first time with my present group, Porno Para Ricardo. However, without considering that, being already with them, I was imprisoned.

Why were you imprisoned?

G: They used the fake pretext of drugs. A girl that would not leave me alone, not for a moment, kept asking for drugs, and just to get rid of her, I arranged to get her two amphetamine tablets. She turned out to be a police informant. In spite of that, amphetamines are legal here: you can get them with a medical prescription at any pharmacy.

How long was the sentence?

G: I was given four years, but I only served two –so many people wrote about it outside Cuba that in the end they let me go before completing the full sentence.

Making punk music is something outside the norm in Cuba?

G: Yes, actually is not in fashion with Cuban rockers. There are five or six punk rocker groups in Cuba, but none of them has gone this far to say the things that we say. Many of them live in the double life, moving between the official music and the extra-official music scene, which is something that does not interest me in the least. Some rappers are a little more open, like in the case of the group Aldeanos. They too use “his” name and the last names and to not resort to double meaning words.

How did you get to rock music in a communist environment and filled with afro Cuban hip-hop?

G: Thanks to schoolmates. At the beginning, I liked popular Cuban music, but when I listened to my school friend’s rock records, I knew immediately that those musicians spoke for me. It was sort of a revelation.

How old were you then?

G: Twelve.

What music inspired you the most?

G: Black Sabbath, Led Zeppelin, Sex Pistols, Iggy Pop, Nick Cave, Velvet Underground, Bauhaus, Joy Division, The Clash, the Ramones…But the first music that I listened to were popular songs, including ballads that my mother would often sing to me.

Do young Cubans know the groups you mentioned?

G: The older ones know about the older generation groups, but only a very limited few know about The Clash or Ramones, for example.

How do you go about getting these records? Because you cannot buy them here, right?

G: No, you cannot buy them. Cubans that are allowed to travel, or sometimes tourists bring them.

How are your fans?

G: We have the same fans that other rock groups have. In Cuba, there is no such a thing a punk rock movement; therefore, anyone that listens and likes rock music comes to our concerts. Since there is no separate forum for punk rock here, the people come to all the concerts.

When was the last time that you played as a group?

G: The last time that we played was a month ago [this interview was conducted in the month of May]. However, we played anonymously –another group invited us to play, without saying a word as to who we were or our name. We are not authorized to play by any means; therefore, we have been looking for some alternative that would allow us to [play] outside the official sphere.

Can you play at private parties, weddings, etc.?

G: To play at private parties and all that, like you suggest, is very difficult and complicated. Although many people like us, there are in a state of fear and the people have panic about inviting us to play or to come here and talk to us. If we play in a private house, it could compromise and destroy its owners. Here many people like our music and would behave normally if it were not for all that, they pretend not to see us in the street, as if one had leprosy for something worse.

Do you have contact with any of the extra-official intellectuals or dissidents? Do they know the group exists?

G: We do not have any type of contact with them, and we would like to contact some of them, because the more constant feeling one has here in Cuba is loneliness and separation. One finds himself on his own in what we do, even when surrounded by friends, which on the other hand is good. However, sometimes one also runs into people that know about the group, although they have never been to a concert, and have never had a cassette in their hands.

What is the social background of the group’s members?

G: Like almost everyone in Cuba, we come from a very poor environment. The communist system has given poverty to the masses. Everything here is equally divided in a very just way. We are all the same in our misery.

When you were in school, did you get into any trouble because of your music or the long hair?

G: When I was in the Pre University, I was accosted, constantly, because I was dressed like a rocker and in certain occasions, they would literately kick me out of the school. They tossed me out to ruin my life and the only effect that it had was that I left school.

Guitarist: I studied mathematics and later I stayed to teach for 2 years. Finally, they decided in a communist youth conference that I was going to be kicked out for having joined the group, even dough I had excellent references from the school.

Drummer: I graduated from the university, but I did not know about the group in those days.

G: He is new to the group, because the “old” drummer decided to separate himself from this environment after he started to receive calls from the police threatening him and his family, and the pressure built, and even his blond-haired girlfriend blackmailed him to leave the group.

How did the group formed?

G: I decided to form a group in 1998. Since I loved rock’n’roll, I thought of doing something that I could tell my grandchildren about, that I did not just listen passively to that music. That is when I found the ex drummer. The friend that you see here used to play bass, and he is the best musician amongst us, but all of the sudden he announced that he was going to start playing the guitar. We were a trio: bass, guitar and drums, which was fine, because while we had few people in the group, it was better for working together. All we need now is a bass player.

Guitarist: Our last bass player left the group, same as the drummer. This is the fourth or the fifth member to quit the group; they feared to continue playing with us.

G: We have even written a son dedicated to all the bass players that have betrayed our group.

Did you have to do military service?

Bass player and guitarist: Yes, we had to do it. After school ended, we served one year.

G: No not me. I managed to find a way of getting a certificate from a psychiatrist that would exempt me from military duty. However, if that had not worked, my plan was to go to the committee of military recruitment dressed as a woman and pass myself as a homosexual, so they would reject me.

What was the psychiatrist’s diagnosis?

G: I am not sure, but something to the effect of being schizophrenic.

What are your plans henceforth?

G: Well, before you arrived, we decided to stop rehearsing for a while and instead of that, we are just going to record.

In 1996, there was a violent governmental operation against underground music in Czechoslovakia, and that provoked that resurgence of an opposition group to the government called Charter 77…

G: That is great! We have been thinking of changing the name of the band so that we could play again in future concerts. We could call ourselves that, Charter 77.

I do not think that that it is a good idea, if you want to remain playing without calling attention to State Security and the police.

Don’t be a full, the intelligence and cultural knowledge of the local agents is extremely low.

Coda

At the end of the interview, what happened in the room without a roof; we asked the group to pose with their guitars for a photo. Just a moment ago, they where talking about the need to stop playing in concerts for a little while. However, once they had those instruments in their hands, they eyes acquired as strange glimmer. They turned on the sound equipment, and the music flowed through the amplifiers and baffles and was heard throughout the entire neighborhood with a shaking roar, accompanied by the voice of Gorki: “Comandante…” [listen to the song, via Penúltimos Días]

«Llegó la hora de llamar las cosas por su nombre»

Gorki Águila, líder del grupo Porno Para Ricardo, afirma que no necesita ningún recurso poético para señalar al culpable del 'infierno que vive Cuba'.

Petr Placák, Ciudad de La Habana

martes 29 de agosto de 2006 6:00:00

Grupo Porno Para Ricardo. Gorki Águila, a la derecha

Después de pagarle a nuestro taxista, entramos en un rascacielos de concreto de la era soviética, descascarado y en muy mal estado. Los rockeros nos esperan dentro. Han estado discutiendo cómo podrán seguir de ahora en adelante con su música. Ayer recibieron una citación de la policía que no presagia nada bueno para su objetivo de poder continuar produciendo un arte libre.

El documento acuñado, que yace visible sobre la mesa, no tiene la menor traza de ser una invitación amistosa.

¿De qué se trata exactamente?, le preguntamos a Gorki Águila Carrasco, cantante del grupo Porno Para Ricardo, en entrevista para 'Encuentro en la Red'.

Se trata de una citación de la policía acuñada con el sello de la República de Cuba, del Ministerio del Interior, de la Policía Nacional Revolucionaria. Está firmada por un tal teniente Torres. Me han dado la orden de presentarme allí mañana a las once.

¿Qué es lo que ellos quieren exactamente de ustedes? ¿Quieren obligarlos a que no vuelvan a tocar más?

Gorki: Todo esto comenzó cuando fuimos acusados de perturbar la paz y la tranquilidad —la policía nos dijo que los vecinos estaban protestando por el ruido que hacíamos de noche. Ahora quieren decirnos algo acerca de las letras de nuestras canciones que atacan a Fidel Castro. Una vez un policía muy cínico nos dijo: "Cualquier cosa que sea lo que ustedes piensen sobre la revolución en Cuba, está prohibido que lo digan en público".

¿Entonces, las letras que ustedes escriben hablan directamente sobre Castro?

G: Sí. Tenemos una canción dedicada a nuestro comandante en jefe, que menciona su nombre completo y dice bien claro que es un hijo de puta. Todo el arte que se produce en este país está, de alguna manera, enmascarado con un doble sentido, y ya yo me cansé de esas letras poéticas llenas de insinuaciones indirectas. Ya llegó la hora de llamar las cosas por su verdadero nombre. Lo que más nos interesa decir en nuestras letras es que el infierno en que vivimos tiene un nombre y apellidos: Fidel Castro Ruz. Ya no necesito de ningún recurso poético para decirlo.

¿Le puedo citar literalmente en el artículo?

G: Claro que sí, por eso es que lo estoy diciendo.

¿Han tocado la canción de Castro en público?

G: No, porque eso sería virtualmente un suicidio. Pero sí la grabamos y al final acabó en las manos de algún oficial. Por eso es que hemos sido citados por la policía. La estrategia de ellos es intimidarnos y obstaculizarnos con la mayor cantidad de medios posibles. Nos han prohibido ya tocar en conciertos y ahora quieren que ni tan siquiera ensayemos.

¿Esta es la primera vez que los interrogará la policía?

G: Esta es la primera vez oficialmente con mi grupo actual, Porno Para Ricardo. Pero sin tener en cuenta que, estando ya con ellos, estuve preso.

¿Por qué fue encarcelado?

G: Usaron el falso pretexto de las drogas. Una chica no me dejaba tranquilo ni un momento pidiéndome drogas, entonces para quitármela de arriba, me las arreglé para conseguirle dos pastillas de anfetaminas. Y resultó que ella era una informante de la policía. A pesar de eso las anfetaminas son legales aquí: las puedes conseguir con una receta médica en cualquier farmacia.

¿Cuánto tiempo le echaron de condena?

G: Me echaron cuatro años, pero sólo cumplí dos —tanta gente escribió sobre eso fuera de Cuba que al final me dejaron salir antes de cumplir la condena total.

¿Hacer música punk es algo fuera de lo común en Cuba?

G: Sí, incluso entre los rockeros cubanos no está de moda. Hay cinco o seis grupos punk en Cuba, pero ninguno de ellos ha llegado tan lejos como para decir las cosas que nosotros decimos. Muchos de ellos viven una doble vida, moviéndose entre la escena musical oficial y la extraoficial, algo que a mí no me interesa hacer para nada. Algunos de los raperos hablan más abiertamente, como es el caso del grupo que se llama Aldeanos. Ellos también usan el nombre y los apellidos de Él y no recurren al uso del doble sentido.

¿Cómo llegó a la música rock en un medio comunista y lleno de hip-hop afrocubano?

G: Gracias a algunos amigos de la escuela. Al principio me gustaba la música popular cubana, pero cuando escuché los discos de rock de mis compañeros de escuela, supe inmediatamente que esos músicos hablaban por mí. Fue una especie de revelación.

¿Qué edad tenía entonces?

G: Doce años.

¿Qué música le inspiró más?

G: La de Black Sabbath, Led Zeppelin, Sex Pistols, Iggy Pop, Nick Cave, Velvet Underground, Bauhaus, Joy Division, The Clash, The Ramones… Pero la primera música que oí fueron canciones populares, incluyendo los boleros, que mi mamá me cantaba a menudo.

¿Son conocidos entre los jóvenes cubanos esos grupos que mencionó?

G: Los más viejos conocen los grupos de generaciones más viejas, pero sólo un círculo muy limitado conoce a The Clash o Ramones, por ejemplo.

¿Cómo se las arregla para conseguir esos discos? Porque no puede comprarlos aquí, ¿no es así?

G: No, no se pueden comprar. Los traen aquellos cubanos a los que les es permitido viajar, o a veces algunos turistas.

¿Cómo es el público que tienen ustedes?

G: Tenemos el mismo público que otros grupos de rock. En Cuba no existe un movimiento punk como tal, así que cualquiera que oye y le gusta la música rock viene a nuestros conciertos. Como no hay un espacio aparte para el punk aquí, la gente viene a todos los conciertos.

¿Cuándo fue la última actuación del grupo?

G: La última vez que tocamos fue hace un mes [esta entrevista fue realizada en el mes de mayo]. Pero tocamos anónimamente —otro grupo que nos invitó a actuar sin decir ni una palabra sobre quiénes éramos o nuestro nombre. No estamos autorizados a tocar de ningún modo, así que hemos estado tratando de encontrar alguna alternativa que nos permita hacerlo fuera de la escena oficial.

¿Es que tampoco pueden tocar en fiestas privadas, bodas, etc.?

G: Tocar en fiestas privadas y demás, como sugieres, es muy difícil y complicado. Aunque le gustamos a mucha gente, hay una atmósfera de miedo y a la gente le da pánico invitarnos a tocar o venir aquí y hablar con nosotros. Si tocáramos en una casa particular, eso pudiera meter en problemas y destruir a sus dueños. Aquí mucha gente que le gusta nuestra música y se comportaría de una manera normal si no fuera por todo eso, se hace la que no lo ve a uno en la calle, como si uno fuera un leproso o algo peor.

¿Tienen contacto con algunos de los intelectuales extraoficiales o disidentes? ¿Saben ellos de la existencia del grupo?

G: No tenemos ningún tipo de contacto con ellos, y en realidad nos gustaría contactar a algunos, porque los sentimientos más constantes que uno tiene aquí en Cuba son la soledad y el aislamiento. Uno se encuentra haciendo en solitario lo que hace, incluso estando rodeado de los amigos, que por otro lado son buenos. Pero también a veces uno se tropieza con gente que conoce al grupo aunque nunca haya ido a los conciertos, y que de alguna manera les han llegado nuestros cassetes a sus manos.

¿Cuál es el background social del que provienen ustedes?

G: Como casi todo el mundo en Cuba, venimos de un ambiente de mucha pobreza. El sistema comunista le ha donado la pobreza a las masas. Aquí a cada cual se le reparte lo mismo de una manera muy justa. Todos somos iguales en nuestra miseria.

¿Tuvieron problemas todos ustedes por causa de la música o el pelo largo cuando iban a la escuela?

G: Cuando estaba en el preuniversitario me molestaban, sin parar, porque me vestía como un rockero y algunas veces hasta me botaron literalmente fuera de la escuela. Me echaron a perder mi vida y el único efecto que tuvo todo eso fue que dejé la escuela definitivamente.

Guitarrista: Yo estudié matemáticas y luego me quedé enseñando otros dos años. Al final acordaron en una reunión de los jóvenes comunistas que me iban a botar por haberme metido en el grupo, a pesar de que tenían muy buenas referencias en la escuela de mí.

Baterista: Yo me gradué de la universidad, pero tampoco conocía al grupo en esa época.

G: Él es nuevo en el grupo, porque el baterista anterior se quiso apartar de este ambiente cuando empezó a recibir llamadas de la policía amenazándolo, y su familia entonces lo empezó a presionar y hasta la rubia que era novia de él lo chantajeó para que se fuera del grupo.

¿Cómo se formó el grupo?

G: Yo decidí hacer un grupo en 1998. Como me encantaba el rock'n'roll pensé que debía hacer algo para poder decirle a mis nietos que no sólo me dedicaba a escuchar pasivamente esa música. Entonces fue que encontré al baterista anterior. Este amigo mío que ves aquí tocaba antes el bajo, él es el mejor músico de entre todos nosotros, pero de pronto nos dijo no hace mucho que iba a empezar a tocar la guitarra. Así que éramos un trío: bajo, guitarra y batería, lo que estaba muy bien, porque mientras menos gente haya en el grupo, mejor se puede trabajar juntos. Ahora sólo nos hace falta encontrar un bajista.

Guitarrista: Nuestro último bajista dejó el grupo, igual que el baterista. Este fue el cuarto o quinto miembro del grupo que lo dejó por el miedo a seguir con nosotros.

G: Hasta hemos escrito una canción dedicada a todos los bajistas que han traicionado a nuestro grupo.

¿Tuvieron que servir en el ejército?

Baterista y guitarrista: Sí, tuvimos que hacerlo. Un año después de la escuela.

G: Yo no. Yo me busqué la manera de conseguir un certificado de un psiquiatra que me daba la baja del ejército. Pero si eso no hubiera funcionado, mi plan era ir al comité de reclutamiento militar vestido como una mujer y hacerme pasar por homosexual, para que no me aceptaran.

¿Cuál fue el diagnóstico del psiquiatra?

G: No sé muy bien, pero era algo así como síntomas de esquizofrenia.

¿Qué piensan hacer a partir de ahora?

G: Bueno, antes de que llegara, decidimos que vamos a dejar de ensayar por algún tiempo y en vez de eso vamos solamente a grabar.

En 1976 hubo una violenta operación contra la música underground en Checoslovaquia, y eso provocó que surgiera un grupo opositor al gobierno llamado Charter 77…

G: ¡Eso está buenísimo! Hemos estado pensando cambiarnos el nombre para poder volver a tocar en conciertos más adelante. Pudiéramos llamarnos así mismo, Charter 77.

A mí me parece que esa no es una buena idea, si ustedes quieren mantenerse tocando sin llamar la atención de la Seguridad del Estado y la policía…

G: No seas bobo, la inteligencia y los conocimientos culturales de los agentes locales son extremadamente bajos.

Coda

Al final de la entrevista, que transcurrió en una habitación sin techo, le pedimos al grupo que posara con sus guitarras para una foto. Un rato antes, estaban hablando de la necesidad de parar de dar conciertos durante un tiempo. Pero en cuanto tuvieron los instrumentos en las manos otra vez, sus ojos adquirieron un extraño brillo. Encendieron los equipos de sonido, y la música de los amplificadores y bafles recorrió el vecindario con un estremecedor rugido, acompañado por la voz de Gorki: "Comandante…".

2 comments:

"The communist system has given poverty to the masses. Everything here is equally divided in a very just way. We are all the same in our misery".

This is the quote many folks need to read and remember when they start commenting about the good things about Fidel and his cronies. Perhaps Lizet needs to read this article as well.

Orlando: Gracias por el comentario en mi blog, lei la entrevista y no sé porqué no me asombra nada de lo que esos músicos dicen ¿Será porque vivi en el monstruo y conozco sus entrañas? En los 70's a mi padre lo encarcelaron por decir que un neumatico de un coche (goma) no servia ni para irse de Cuba, con esa frase dicha en público, armaron un caso de intento de salida clandestina y le echaron cinco años, de los cuales cumplió tres.¿Así son las cosas en mi país!

Un abrazo

Post a Comment